For decades, BMW assiduously avoided ever building a motorcycle that could be directly compared to the models of other manufacturers. Sometimes this resulted in idiosyncratic excellence, like the 1985 K 100 RS; sometimes it sent their engineers down a bit of a rabbit hole. The average age of a BMW buyer, meanwhile, remained around 50 years old. But a 50-year-old in 1985 had cut their teeth on air-cooled Japanese or worse, British, bikes. A 50-year-old rider in 2005 grew up on FZR600s and GSXRs.

In 2006, the General Director of BMW Motorrad, Hendrik von Kuenheim, threw caution to the wind and built the S 1000 RR, a transverse four-cylinder, aluminum-framed, conventionally suspended sport bike that, from the spec chart, was directly and favorably comparable to the offerings from Japan down to the price point.

While sport bike riders greeted the bike with enthusiasm, it confused the branding a little for the Aerostich adventure customers because now the brand wasn’t just for stodgy riders, it was for racers, track day enthusiasts and, of course, bike night poseurs.

While these dynamics convulsed the BMW faithful, the S 1000 RR cast a beacon throughout Germany beckoning the brightest and most dedicated to come and work at BMW. The adoption of the S 1000 RR into BMW’s arsenal planted acorns inside the company; their roots would eventually grow and split decades-old traditions and permeate the organizational chart at BMW Motorrad to the highest level.

Twenty-odd years after the BMW gang walked out of the first S 1000 RR design meeting, BMW has gone from being the stodgiest of brands to the absolute height of exuberant sport riding. This is easy to do in advertising. It is much harder to do in actuality.

All of this led to me arriving at the Cremona Race Circuit in Italy in the middle of the World Superbike weekend. It wasn’t clear to me what event I was attending because, as it turned out, an event like this–at least in this moto-journalist’s 30-odd years of experience–had never been attempted, much less by BMW!

We were given relatively unfettered access to the ROKiT World Superbike Team with reigning world champion Toprak Razgatlioglu and Michael van der Mark as well as the techs, execs, and mechanics for the team. Also in attendance were a dozen BMW Motorrad execs, project managers, software engineers and the like, along with execs and mechanics for alpha Racing. Alpha has a direct supply of BMW base parts (engines, etc.) from which they build various iterations of M 1000 RRs, including their MotoAmerica Stock 1000 bike (which I previously tested) as well as a superbike version, which Cameron Beaubier is using to lead the MotoAmerica Superbike championship.

While reveling in the pageantry of the World Superbike weekend, I was preparing to suit up the following day to ride the M 1000 R, M 1000 XR, M 1000 RR, alpha Superstock, alpha Superbike, World Endurance bike, and…Toprak’s factory World Superbike!

If all that wasn’t enough, every BMW or alpha employee I chatted with, from the CEO of BMW Motorrad Markus Flasch to BMW Project Manager Aline Lorch or her husband Andreas (vehicle control software), were not only huge motorcycle enthusiasts, but would be riding on the track with us. Markus, using that oak tree planted 20 years ago, had apparently been thinking for a year since he took the top seat of doing the ultimate track day, not just for us spoiled journalists but for his own people as well. Many of the staff new to BMW over the last 15 years came in no small part because they wanted to work for the company producing the excellent S 1000 RR. You can’t fake that type of love of motorcycle joy–it’s written into the mitochondrial DNA or it’s not. If your whole company loves motorcycles, you are more likely to release M series bikes and less likely to release the 1978 R 45.

BMW was abundantly clear this day was not a press launch, which is convenient, as it would have been like trying to drink from a firehose. Also, showing a non-Germanic flexibility, the Monday riding schedule was thrown in the shredder as there was an impending rainstorm, temporarily held at bay by the Apennine mountains, but, once that obstacle was overcome, our track would quickly get wet. The four race bikes (two alpha bikes, the World Endurance bike, and the factory World Superbike) would be restricted to an out lap, a hot lap, and an in lap.

We were rocking Pirelli soft slicks on all the race bikes (and the M 1000 RR) and they reversed the shifting on all the bikes but the XRs. I decided to try to ride only GP-shift bikes until the end of the day and to work my way from slowest to fastest. I started the day on the M 1000 R, the naked version of the S 1000 platform but sporting some nicer parts to take it to the “M” specification to follow their famous sporty car branding.

M 1000 R

I had always been M 1000 R curious, but I thought I would ride one on the street sometime, not the Cremona racetrack. The M 1000 R is pretty fancy. It has carbon wheels, aerodramatic downforce via winglets, and blue caliper brakes. It’s got a lot of support in the suspension, so there is a lot of spring and a lot of damping. All of that means it feels great on a racetrack. I am not sure how it would be on a dirt fire road, but I would be happy to find out sometime! Despite being a roadster with low tube handlebars, they reversed the shifting, so it felt really natural at the track. There is only one long straight at Cremona, so the lack of a fairing meant there was only one place on the track where the wind blast was trying to rip my head off. The bike handled riding at a racetrack very well.

Even on my first laps, when the track topography was still a mystery, I could corner pretty hard on the Pirelli Corsa tires, which quickly came up to temp and started balling up nicely. Tube bars make for a slightly awkward riding position, but as I was trying to learn the track as well, I just started laying off the brakes and throwing the thing into turns. I was knee-down on every turn on lap two.

I think, perhaps, that even the ridiculous-looking winglets were working. As I would shift my weight back onto the seat, coming onto the back straight, the bike would get a little speed wobble, but if I kept the power on and the speed increased, the bike grew more stable. I mean, I wasn’t exactly following the proper scientific method, but I relate the anecdote nonetheless.

If we were riding around the spectacular mountain roads of Italy, the R is the one I would grab. The only thing that would make the bike a little better for multi-day rides would be a little frame-mounted fairing and maybe hard bags–but there isn’t any reason to shy away from tracking your M 1000 R to learn just how capable the platform can perform.

M 1000 RR

There was a little bit of a free-for-all grab bucket vibe to get one of the stock BMW M 1000 RRs. These bikes had Pirelli 0-compound soft slicks, requiring the bike to be on stands with warmers if it wasn’t on the track. The pit crew stayed busy.

As I go about my daily life, I try to maintain some level of self-awareness, so it was amusing to be aware of the stock $41,000 M 1000 RR being, you know, kind of plain compared to the race bikes sitting on the other side of the garage.

In an absolute sense, the M 1000 RR is exceptionally fancy. It’s got a ton of carbon parts and, even as a street legal production Euro 5+ compliant motorcycle, it’s not built to a low price point, so it doesn’t have many component compromises. It’s got really nice electronics with dynamic traction control and wheelie control. The auto blip electronic throttle valves meant I only had to use the clutch leaving pit lane and even if I got lost on the track and needed to downshift mid-corner at 50 degrees of lean, the bike would sort it out for me.

I don’t know if it was the Italian sunlight and the Italian track and the Italianish slicks, but the bike was working really well. Jumping from the R to the RR, I thought it would feel more natural given my proclivity for clip-ons, but at first the RR felt cramped because the R has tubular handlebars bars; it’s a lot roomier.

The other thing I realized was how the R lulled me into a lazy and lugging style of street bike riding by leaving it in third in the slower turns and letting the torque pull me out of the apex. The RR reminded me to drop to second for the tighter turns and smudge rubber on the track with the TC and just rev the nuts off of it through the tight turns.

The bike itself is pretty amazing. It’s an expensive motorcycle, but it works like an even more expensive motorcycle. It steers quickly because of the carbon wheels. There is no chatter. The electronic strategy for the engine braking makes for drama free corner entrances, even with late auto blip downshifts to second. The suspension provides a lot of support, so it’s possible to ride harder than most people can imagine on the stock bike and still have a wide safety margin to avoid having to replace any of those gorgeous carbon body panels.

alpha Racing M 1000 RR Superstock

My father used to say, “I’d rather be lucky than good.” In the summer of 2024, I was fortunate enough to have an alpha Racing M 1000 RR Superstock bike almost to myself for a day at Sonoma Raceway in California.

The typical production race bike build means buying a showroom bike and then removing the insanely expensive catalytic exhaust, bodywork, lights, handlebars, rear sets, suspension, engine covers and, perhaps, wiring harness and ECU and myriad other parts, then putting them in a pile in the garage. You tell yourself you are going to sell all of it, but you never do.

alpha receives bikes from BMW with, in effect, an engine, frame and cooling system, then finishes them with a bespoke wiring harness, ECU, suspension, bodywork, handlebars, etc. The net result is an expensive bike presenting as a bargain because you don’t need to buy all the stock parts you end up throwing away.

I was only going to get three laps around Cremona on the Superstock bike, but I knew what to expect. I knew it was light and fast and the ECU programming was going to be great. I knew the ECU strategy meant only two throttle bodies would open off-idle at full lean–making a funny noise–but as soon as the suspension was loaded and I took away lean angle, the other two butterflies would open and the bike would accelerate as hard as the wheelie control and traction control would allow. The Pirelli slicks allow for a lot of acceleration, so the bike goes HARD out of turns.

Cremona Race Circuit is pretty flat, so there were not a lot of topography-induced wheelies and even when that happened, the ECU intervention to limit the power was smooth. The fueling on the stock emission-compliant M 1000 RR is impressive but, it’s no match for a track-only flash with rider-friendly richness on the injectors. With the extra weight of the street bike shed, the alpha bike almost felt nervous until I realized the turbulence was me putting extra steering input into the bars. Once I realized how much faster the alpha bike steered compared to the stock M 1000 RR, the wiggles went away.

Lap times have an inflection point where each increment faster costs more and more money, and also requires more and more rider talent. The alpha Racing superstock bike is well off the flatlands on that cost-and-performance inflection point, but the vast majority of riders would be hard-pressed to see a lap time difference between that bike and, say, the BMW World Superbike. Two of the riders who are good enough are Jayson Uribe and Andrew Lee. They are currently tied for points and both on OrangeCat Racing’s alpha BMWs, leading the 2025 MotoAmerica Stock 1000 class. That bike starts at $51,500 plus tariffs and shipping and such, but for pure racetrack lebensfreude, it is a good value because it costs only 25% more than the stock M model.

alpha Superbike M 1000 RR

I jumped off the alpha Superstock build and onto the alpha Superbike build. This bike has a different frame, swingarm, electronics, a higher performance–but still factory BMW built–engine, and a whole host of other upgrades. It also costs a cool $116,000 MORE than the Superstock bike. At this price you are well up the curve on diminishing returns but, if you want to lead the points in the MotoAmerica Superbike championship with a top rider like Cameron Beaubier, who has won three out of four 2025 Superbike races at press time, it might be the least expensive bike capable of winning a MotoAmerica Superbike race.

To prepare Beaubier’s BMW, alpha Racing flies an electronics tech from Germany to America for each round of the series to optimize the electronics mapping. Serendipitously, I sat with Michiel Rietveld (also a track and street rider)–that very technician–at dinner and he told me all about the mapping process.

But first, a brief history of race bike electronics. Twenty-five years ago, when we went from carbs to fuel injection on race bikes, the mapping was pretty simple, as we were only working on ignition curves and air/fuel ratios. Those were pretty much solved problems by 2005. Then we started getting traction control to help riders get on the throttle earlier in the corner. In the beginning that was just done through spark kill based on the delta of the crankshaft speed (the system currently still used on dirt bikes with TC), but then we started adding wheel speed sensors, then Inertial Measurement Units, and electronic throttle valves (butterflies), which means the grip throttle is only a signal generator for the engine control unit ultimately deciding, based on programmed coefficients (base maps) and then dynamic signals (wheelie, slide, roll, pitch, yaw) exactly how much to open the actual engine butterflies.

Although most series prohibit GPS inputs to ECUs (which would allow referential position track mapping, e.g., “if the rider is on this bump do this but if the rider missed the bump do that”), so the hack to get to turn-by-turn engine mapping is to create strategies based on meters past the start/finish line with an automatic reset to the finish line each lap to account for long laps or running off or something like that.

Michiel told me about the turn-by-turn mapping available on the alpha Superbike, so I asked if they were using a different traction control (which, remember, is a 3-D map of lean angle, rpm, throttle position, and gear, plus deploying spark kill, butterfly modulation and split throttle body strategy) per gear per corner.

“Usually if we have a good TC strategy for second or third gear it is the same for the whole track, but we spend a lot of time on engine braking,” he said.

We riders used to manage the corner entrance four-stroke slide, which is also when the rear tire surface temperature is at its highest, with manual clutch modulation and setting the idle on the bike high. Then we invented slipper clutches with tunable springs and ramps and clutch pack thickness, but then we got to those electronic throttle valves and (when we can pry control of those ETVs away from the killjoys at the EPA and European Union) allowing all sorts of chicanery. On our older BMW race bikes, we would burn up an $800 clutch in about 10 hours of racetrack use because the plates started slipping so much at corner entrance. Now our clutches last a whole season because the throttle valves are opening slightly to control the corner entrance and the clutch stays fully engaged unless something really bad has happened.

With spec tires (used in many series) and performance balancing in World Superbike, it is harder and harder to find a place on the track to give your rider an advantage. Corner entrance and apex, greatly assisted by the confidence of a stable back end of the bike, means there is an advantage to be gained by flying a guy from Germany to the USA for each round to look at the data traces and change a few numbers on a configuration file because of the advantages over not doing that. They even have engine braking maps with grip throttle position, gear, RPM, and distance from start/finish.

I asked him, “Do you ever think ‘I could just remote desktop into the bike from Germany and do the same thing without the jet lag?’”

“I’ve done it before, but it’s better when I can hear everyone talking at the track,” smiled Michiel.

This will all seem quaint in a couple more years when we have AI doing multifactor regression analysis on massive data sets and automatically configuring the ECU, kind of like they are already doing in MotoGP, including incorporating 3-D track scans. But all the maps were already built for this bike, so the first thing that struck me was the extra lever on the right grip. Because, for the first time in my 42 years of riding, I encountered a bike with neutral underneath first gear (or on top of it depending on how you are looking at it) with a lockout so the shift pattern is N – 1- 2 not 1- N – 2. This is, of course, to avoid losing a race by hitting neutral unintentionally.

Is the alpha Superbike better than the alpha Supersport bike? Yes it is, but remember at this point we are sharpening a straight razor. Riding the Superbike made me realize there were little bits of movement on the Supersport bike which were absent on the Superbike. That stability, which is an incredibly complex blend of tensile material strength, tire, spring, damping, weight distribution, split throttle body opening off the apex, engine braking, all of it, just communicates to the rider that it is fine to brake later, turn harder, lean more, and to get on the gas earlier. Confidence = encouragement = faster lap times. Then a top talent like Cameron Beaubier can extract the maximum performance out of the race package and, when he does that, he wins the American Superbike races.

We can empirically quantify what the extra money gets you, not including the tuning and setup budget, at Road Atlanta on May 4, 2025. Cameron Beaubier was 0.4 seconds a lap faster than any other Superbike, winning the race by 2.3 seconds over 19 laps. Notably, he was also two seconds a lap faster than Uribe and Lee, who were P1 and P2 on alpha Superstock bikes on the same day.

If the rules allowed it, there isn’t a top team racing in the world not willing to happily pay $100,000 for two seconds a lap.

The Unobtainium ROKiT BMW 2025 World Superbike (Toprak’s bike)

There are moments in my personal journey where I have to take a moment to appreciate the rare air I am breathing. Standing in the ROKiT World Superbike garage–in my leathers– impatiently waiting for the most expensive three laps I’ll ever turn, I stopped to consider that this M 1000 RR wasn’t just a bike; it was the physical manifestation of a huge system which all had been choreographed and timed for an ephemeral six minutes.

“Neutral is at the bottom of the shift pattern, you need to thumb the lever on the right grip to get the bike in neutral. It’s GP shift. There is a rear brake lever for your left thumb if you want it. This is one of Toprak’s three bikes, so please don’t crash it.” At least I think that’s what the crew chief said. I was too busy absorbing the technical details of the support systems. Another example is that the engine control unit does so much heavy lifting (maybe not when I am riding it, but certainly when Toprak is) it gets its own air vent to keep it cool.

Race tires only work within a specific temperature range and the carcass of the tire is designed to work at a specific pressure, which can change if the tire gets hotter or colder. Whereas surface temperature of a tire will jump in milliseconds, the carcass has a few more seconds of thermal mass to it. Thirty years or so ago we adopted electric tire warmers to bring race tires up to temperature before the start of the race, and it is common to obsess over cold tire pressure, off-the-warmer tire pressure, and off-the-track tire pressure, all cross referenced with tire temperature to make sure the pressure and the rubber temperature are within their designed operating range.

In the World Superbike garage they want NO pressure rise from the warmer to the track, which means they store the wheels–with the tires mounted–in an oven with a tire warmer mounted to not only bring the thermal mass of the tire but also the rim to the ultimate pressure and temperature they want to run on the track.

Toprak’s bike is fitted with endurance-style quick-change systems front and rear–meaning the spacers are captive to the wheels and there are ramps on the bottoms of the front forks with the front fender mounted on swivels. A front wheel, even with its HUGE 335mm front rotors, can be installed in seconds with the calipers in place. The rear is simpler, with a captive underslung caliper and ramps.

While the bike sits on stands with no wheels installed (they’re still in the oven), an umbilical cord of a network cable drops from the ceiling to the dashboard, which is monitoring the health of the electronics system and sensors. Standing around the bike with a laptop would create unnecessary traffic by the bike, so the computers monitoring the data are in the back corner of the garage.

Virtually all road racing series have rules. Although I personally find performance-balancing rules (different manufactures get different RPMs and fuel flows to make the slower bikes more competitive) to be a bit dysgenic, I understand it makes for better spectacle. Up to the limits of the rules, the components on Toprak’s bike are clearly of the best possible quality. The heat-dispersing Brembo front brake calipers are $16,000 each. The brake discs are not only huge, but thick. The backing plates on the brake pads resist warping. The carbon subframe, the electronics, the carbon bodywork–everything is the highest quality available, and then it is assembled by some of the finest mechanics in the world.

When the bike arrives at the track, the electronics engineers and suspension engineers refine the set up based on Toprak’s feedback and the myriad sensors collecting data on the bike allowing for fine tuning of engine braking, traction control, and power trim, while also fine-tuning spring and damping set-up on the top-end Öhlins forks and shock. After two days of programming and set-up, the mechanics get to the garage on Monday morning and mount new Pirelli slicks and put them in the oven to warm and carefully measure fuel into the tank. Not including the initial engineering, just to get to my three laps required over 200 hours of combined preparation work on the bike for this moment. “Please don’t crash it,” indeed!

They carry the wheels fresh from the oven and effortlessly install them on the bike, then send Toprak out to take one sighting lap to ensure all systems are go.

I knew I only had three laps. Aware I had never crashed at a press launch, I said as much just before I swung a leg over the bike. I wanted to balance the sheer exhilaration of the highest quality three laps of my racing career.

“Let us push you out of the pits a bit before you drop it into gear to save wear on the transmission,” I heard a mechanic say.

This Superbike transmission has the N – 1 – 2 shift pattern and the lockout lever to find neutral. In the last 20 seconds of waiting, I wondered if the internal ratios for the transmission were different from the alpha or M bikes I had been riding; over the exhaust note and with helmet and ear plugs installed, I called out, “Toprak! First or second for the slow turns?”

“Second!” he shouted as the mechanic started pushing me forward. I tried to shift to first as gently as I could and off I went.

Robert Pirsig famously went crazy riding a Honda 250 and contemplating the concept of quality on a cross-country motorcycle trip as immortalized in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. In the modern world of CNC, Autocad, de minimis shipping from China, well-intentioned and misguided vehicle regulations, and lowest common denominator design criteria, a perfect product benefitting from perfect service and perfect preparation for use in exactly the right moment and in exactly the right conditions is a rare thing indeed.

Every component is the highest quality one can get for production-based racing. Between the brakes, engine, ECU, and the lightest and/or strongest chassis with fully-developed vehicle dynamic software, mapped corner by corner for this track, the bike is crazy easy to ride.

The ergonomic position felt immediately comfortable for my 5’10” frame, with the foot pegs, levers, and clip-ons just where I wanted them. Aware I only had 39 turns to experience this exquisite machine, I put it on my knee on the first turn out of the pit lane. The steering was perfectly neutral. It didn’t steer fast or slow, and there was not a twitch or wiggle to the input. It was like the bike was on a gimbal. As I went back to the throttle for the first time, at 50-odd degrees of lean in second gear, I wondered what superbike horsepower was going to be like.

At first touch, the electronic throttle bodies only open on two cylinders, giving a nice crackle through the exhaust pipe and just the tiniest bit of rotation from the rear of the bike. As I took away lean angle, the ECU steadily opened the other two butterflies until all four were singing in a powerful, resonant chorus simply eating the next short straight almost before I could get back up on the seat.

We don’t call them “brakecycles,” but if you think about it, the brakes have more relative energy work to do than engines around a race track. I thought I had been riding on very good to excellent brakes all day before I experienced World Superbike brakes. Not only are they subtly responsive to allow holding just the right pressure on the tire and keep the fork in just the right spot into the turn, but they basically don’t heat up. I mean, they do, but the heat has no bearing on how the brakes work. Not just from turn to turn, but at the end of the sixth-gear back straight, braking hard down to second gear, the feel from the brakes doesn’t change from first pull to the apex. Then again, just the brakes on the WSBK BMW cost about half of an entire new M 1000 RR.

It has no movement in the chassis, ever. There is no slip, no slide, no reflection of energy from the tire to the bars, no little oscillations–just solid confidence. Imagine walking up a stone staircase instead of wood. All those little movements are just absent, with the bike imploring you to turn later, open the throttle earlier, lean more, brake a deeper on the side of the tire… and the bike never moves. The capabilities of the bike are so high that, in my one hot lap, there wasn’t a question of exploring those limits. I simply enjoyed the blisteringly fast but totally linear engine, the incredibly sharp but perfectly stable handling, and the enormously powerful but totally linear brakes. The ECU maps were ubiquitous, so I didn’t have to remind myself to trust the wheelie limitations, power trim, or traction control. The confidence was just there.

Toprak can find the limits of this bike, but there are probably fewer than 30 other riders in the world who wouldn’t run out of talent before this bike, assiduously prepared by premier technicians, using the best equipment, runs out of capability.

World Endurance M 1000 RR

Fresh from a race at the Le Mans 24-hour the weekend prior, BMW drove this World Endurance bike from France to Italy to allow us to gawk at it and ride it for three laps. On any other weekend, this bike would have been my primary focus, as my cultural love in road racing is endurance racing. For a three-lap test–and sitting next to all the sprint bikes–I was appalled at my reacting to her like she was a plow horse at the Kentucky Derby.

That said, the bike is incredibly trick and dripping with technology. It also had the larger 24-liter World Endurance tank, which extends under the seat and seemed to place me a little higher up than the other race M 1000 RRs. Also, this bike was rolling on Bridgestones and the rest of the fleet was rocking Pirellis, so it’s a little tough to ascribe the handling feeling on the Endurance bike to its character rather than just being on tires with a different carcass, shape, and compound.

All that said, the Endurance bike had a unique feel that took a few turns for acclimation. It was stable, but steered slower than the sprint bikes. We often have to compromise our endurance bike race set up from a “fast lap” mindset to a “make sure there are still tires left to go fast before it runs out of fuel at the end of a stint.” This sometimes means putting more emphasis on rear wheel mechanical traction than a more front end steering setup.

I’d like to think that Hendrik envisioned its transformation of the BMW ecosystem when he embarked on the S 1000 RR project two decades ago. On these two days, when the boundaries between work and passion blurred, when the thrill of the ride transcended job titles and status, the experience was a celebration of BMW’s spirit of motorcycling and a reminder of their acceptance of the challenge of competing toe to toe with the world’s best.

Comments about Sam’s article? Join the conversation in the MOA member forum.

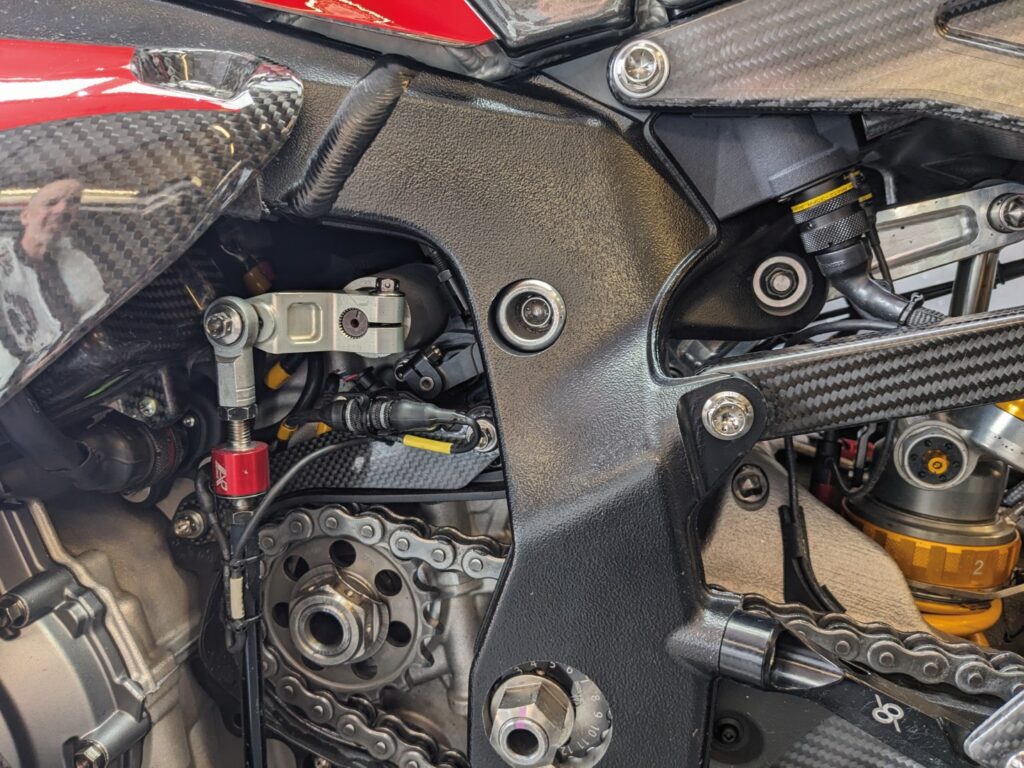

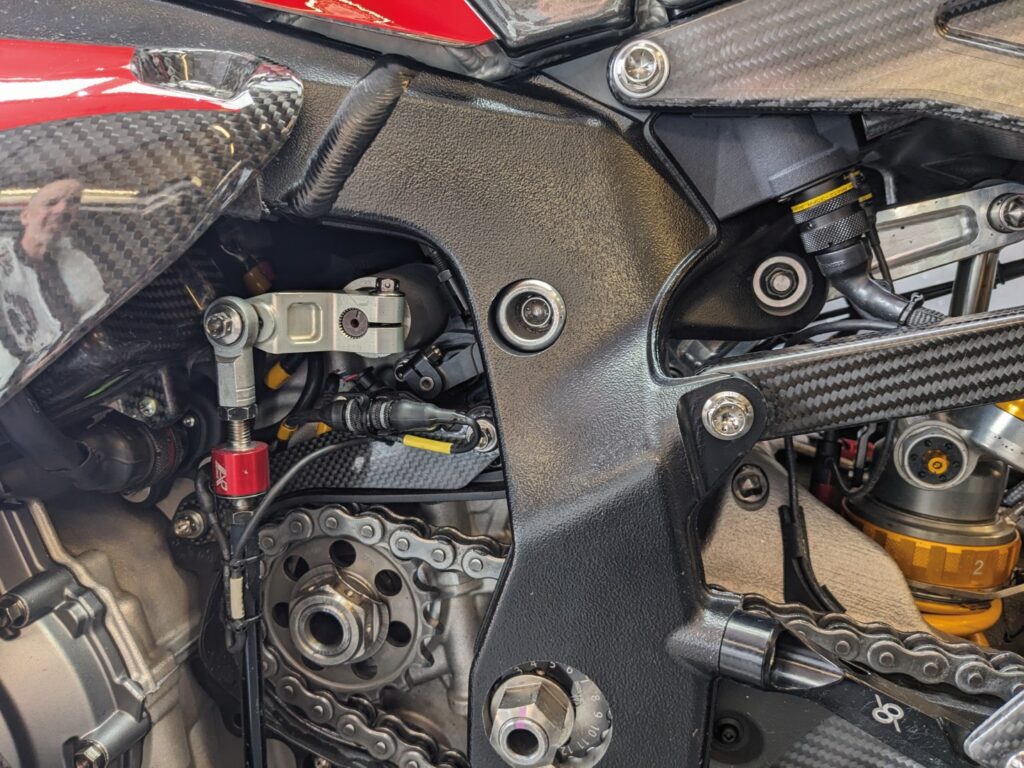

serviced both quickly and copiously. Note the red shift position transducer, the carbon fiber subframe,

the robust metal electrical connectors and the adjustable swingarm pivot set neutral and forward. The

artist is discernible in the reflection in the carbon on the left.

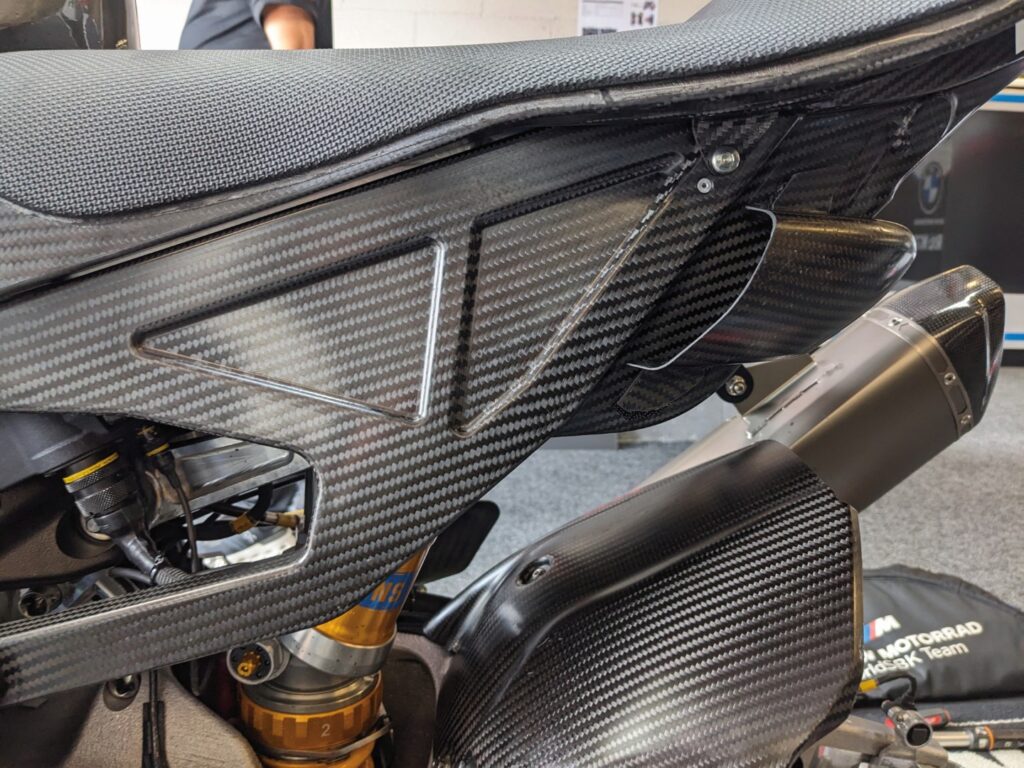

whole rims. This is the latter.